Sterna caspia - about the species

Caspian terns can be found on all continents, except for Antarctica, where they breed and winter on the coastlines and beside inland bodies of water. In North America terns breed during the summer months nesting in colonies of various sizes on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts and at many inland localities (e.g. the Great Lakes) [9]. They prefer to nest in sites that tend to be unstable and are susceptible storms, floods, erosion, desiccation and human disturbance and so exhibit low nesting site fidelity and are able to adapt to new sites easily [8]. These types of sites include sparsely vegetated flat rocky or sandy islands, beaches, and shores. Their nests range from a simple divot to an elaborately decorated depression in the sand or rocks, but being on the ground they are susceptible to changing water levels, predation, and human interaction. After breeding in North America they migrate in the fall to spend the winter on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of Central and South America [9].

nesting colonies

Adult Caspian tern feeding fledgling on East Sand Island

In the Western United States, Caspian terns have not always inhabited the coastlines; before the 1920s they were known to breed exclusively around inland lakes and wetlands. The first recorded coastal colony was in the late 1920s and the 1930s in San Francisco Bay, California, and by the 1950s they had spread all the way to the coastlines of Washington. Shortly thereafter the North American Pacific Coast population experienced a 70% increase to roughly 5,700 breeding pairs in twenty-three separate nesting colonies. During this increase the population also experienced a shift in colony type from small inland colonies to larger coastal colonies mostly at anthropogenic sites (dredge material disposal islands). This trend has continued and is a driving force in the situation on East Sand Island in the Columbia River Estuary [8].

feeding behavior

The Caspian terns' diet consists mainly of fish. They are plunge-divers who catch their prey in shallow surface waters submerging completely [9]. They are able to forage over long distances and certain studies have even record distances of up to 70 kilometers [6]. However, it has also been shown that parents providing for their chicks during the breeding season must be able to protect their chicks from exposure and predation as well as foraging to provide for them, and having to forage for a length of time (i.e. over long distances) means the chick is unprotected for longer periods and may be adversly affected [8].

Oncorhynchus spp. - about the genus

O. mykiss, juvenile

The genus Oncorhynchus in the Family Salmonidae includes the Pacific salmon and the Pacific trout. Of these the salmon and one trout are anadromous, which means they spend part of their lives in fresh water and part in saltwater. Historically, six species of Oncorhynchus inhabited the Columbia River system, but today only five remain: sockeye (O. nerka), coho (O. kisutch), chinook (O. tshawytscha), chum (O. keta) and pink and steelhead (O. mykiss) [2].

life cycle

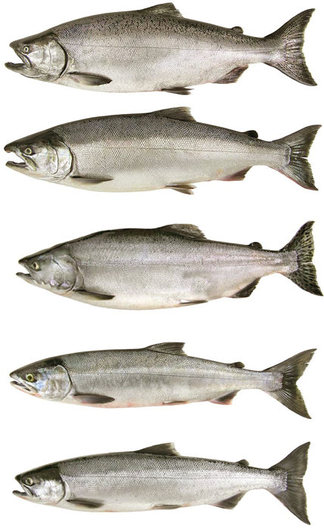

From top to bottom:

Chinook, Coho, Pink, Chum, Sockeye

In anadromous species, adult fish spawn in late summer and fall in freshwater burying their eggs in the lake or stream bottom where the embyro develops. The following spring the juveniles emerge as "fry" and are, for the first time, dependent on external sources of food. At this stage some species migrate into the estuary while others may not migrate for months or even years. Right before migration the fry undergo smoltification, a stage of transformation from a juvenile adapted to fresh water to one that is adapted to estuarine and saltwater. Smolts pass through the estuary and experience an oceanic life stage from one to seven years, depending on the species, where most of their growth is carried out and they become adults [1]. Once mature they migrate up river to spawn in the same location in which they were born. Afterward, they die, and the cycle repeats [10].

Salmon populations in the Columbia River have notably declined from historical values; it is estimated that 100 years ago, between 8 and 16 million adult salmon returned to the river every year to spawn. Today the numbers have been estimated at around 2.5 million adults, most of which are hatchery stock [1]. Many factors caused this decline and likely contributors include habitat loss and fragmentation, overfishing, hydroelectric dams, competition with hatchery fish, and pollution, climate change, increased predation, and changing oceanographic conditions, all of which can, in some way be attributed to anthropogenic influence [11].

Salmon populations in the Columbia River have notably declined from historical values; it is estimated that 100 years ago, between 8 and 16 million adult salmon returned to the river every year to spawn. Today the numbers have been estimated at around 2.5 million adults, most of which are hatchery stock [1]. Many factors caused this decline and likely contributors include habitat loss and fragmentation, overfishing, hydroelectric dams, competition with hatchery fish, and pollution, climate change, increased predation, and changing oceanographic conditions, all of which can, in some way be attributed to anthropogenic influence [11].